This would have to be one of the strangest books I’ve ever read, which might explain why I couldn’t find it on the inter library loan system. The strangeness is highlighted by the fact that the story ends in 1970 when Hughes jets off to the US to become art critic for Time Magazine. One would have thought that 513 pages would have been sufficient to cover his entire life, rich and varied as it was, but no. Perhaps there was meant to be a second edition, although he completed this one six years before his death.

Robert Hughes (The Guardian)

Those who remember the Australian art critic and writer Robert Hughes (1938 - 2012) will recognize the irony in the title “Robert Hughes - Things I Didn’t Know”. He was known for his forthright, even rambunctious views on just about everything. But the book begins with a harrowing account of his near fatal car crash in the north of Western Australia in 1999. It seems we had a different Robert Hughes, physically and in other respects after that episode.

He had a Catholic upbringing and was educated at a strict Jesuit boarding school. For mine, he banters on for far too long about his early life. His distant father whom he clearly idolised was a World War One fighter pilot and later became a solicitor before dying when Robert was only 12. Hughes was the youngest of four by far and his father’s death affected him greatly. Although he rambles on and on about his father’s wartime experiences, Hughes does come up with some interesting anecdotes. Such as Allied high command’s point blank refusal to issue its pilots with parachutes, for the dubious reason that such safety devices would reduce the fighting spirit of the pilots and give them an easy way out. “This appalling callousness condemned many pilots to be roasted alive, thousands of feet in the air, as their stricken little planes spiraled helplessly to earth…” Apparently, some pilots chose to simply bail out without parachutes - who could blame them.

Riverview St Ignatius College, Sydney

The eloquence of Hughes’ writing is evident in his summation of the futility of WW1 and the contrast to the objectives of WW2. “Hitler had to be stopped, and his defeat did save the human race from unimaginably worse slaughters. No such historical necessity excused the deaths of millions of boys in 1914-18. Because of the killing by a Serbian terrorist of an Austrian archduke whose life wasn’t worth a jackeroo’s finger, because of the ineptitude of Europe’s civil and military leaders and the indifference of old men (including British Prime Minister Lloyd George - I believe) to the fate of the young, they were sucked into the immense vortex of the most vilely useless mass conflict in modern history…”

Hughes found life in the Jesuit boarding school, Riverview in Sydney, repressive and beatings were common. However he heaps great praise on Father Wallace who was the headmaster and who allowed Hughes access to books that were outside the limited curriculum of the college. Father Wallace paved the way to Hughes becoming a fully articulate writer.

As Hughes tells the story, he attained the role of art critic almost by accident. His predecessor at The Observer in Sydney was sacked after being critical of an exhibition which, as it turned out, he hadn’t seen. Hughes was an illustrator for the magazine and that was good enough for the editor, the celebrated social commentator Donald Horne. But as Hughes explained, there was very little art in Australia in the late 1950’s and early ‘60s to be critiquing. He also briefly wrote criticism for, and contributed cartoons to The Mirror, until Rupert Murdoch took it over and slashed his wages.

Ian Fairweather on Bribie Island c 1966 (Art Gallery of New South Wales)

One of his more amusing anecdotes involved a trip with the artist Jon Molvig to visit the “sage of Bribie Island”, Ian Fairweather. The trip was hair raising enough due to Molvig’s heavy drinking, but upon arrival they discovered Fairweather in a disheveled state, his front teeth were missing, one foot was wrapped in rags after he’d been bitten by a goanna and he was living in leaky Balinese huts. It was obvious to Hughes and Molvig that the foot was gangrenous and they had to almost drag him to the mainland for treatment.

So appalled was Fairweather’s Sydney dealer with the state of his paintings, she sent him a roll of the finest Belgian flax canvas which would have cost a fortune. Fairweather used the canvas to plug holes in his hut and went on painting on damp cardboard with house paint.

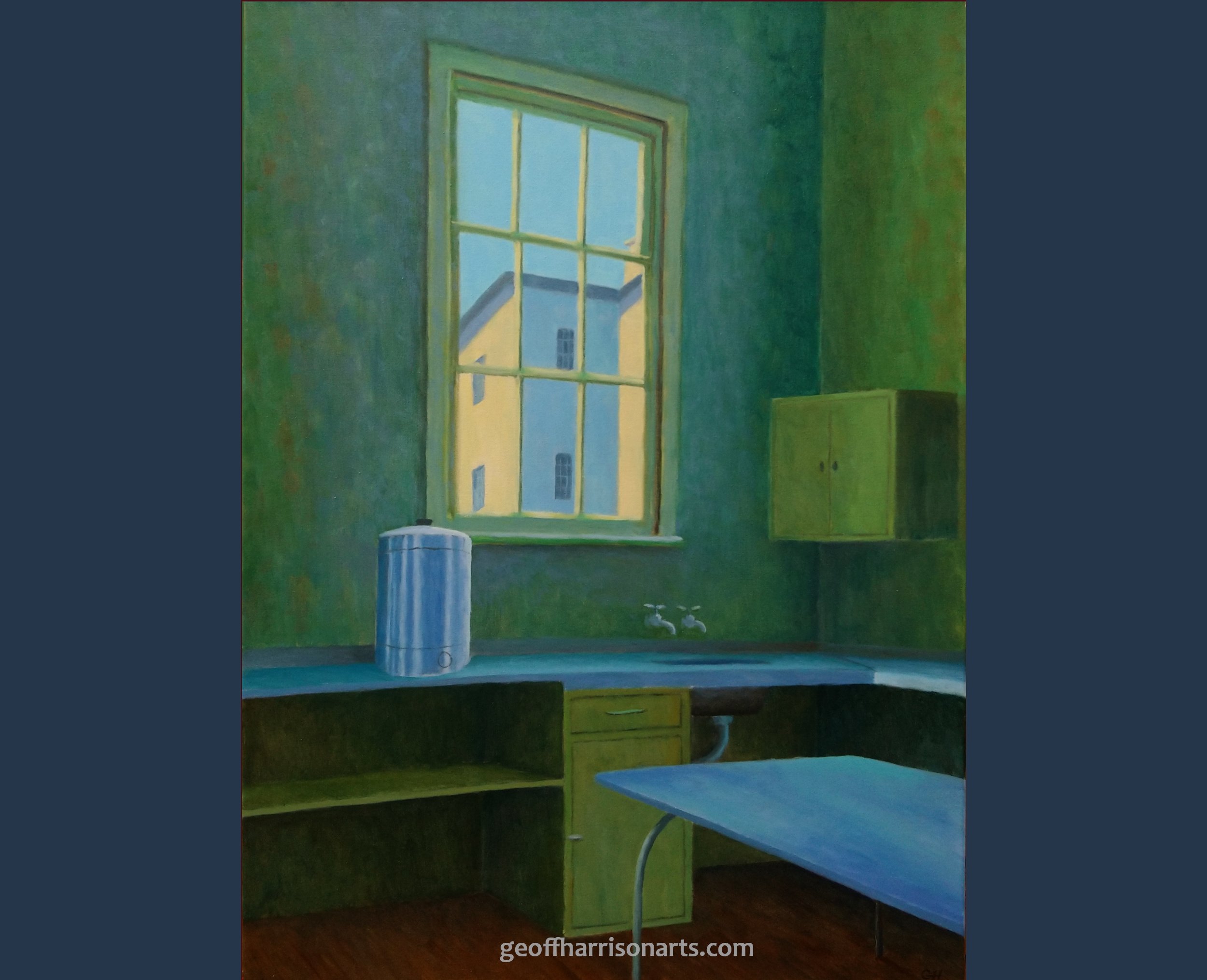

Hughes never felt comfortable in the Australia of his youth. He disliked the bush and the beach - inside a house, or even better a cafe seemed to be his natural habitat. Eventually he realised that he had to head off overseas. He left for Europe in 1964.

Thanks to contacts he developed with the likes of renowned Australian author Alan Moorehead and art historian Herbert Read, Hughes began his writing career. He is particularly indebted to Moorehead, having spent some time living with him and his wife in Italy. He writes at great length about the impact Italian culture had on him (particularly the gardens of Bomarzo), which he was able to enjoy before these sites were “wrecked” by tourism. But he believes that his years in central Italy, being exposed to great religious art, had transformed him from a guilt ridden, young ex-catholic who was haunted by the critical gaze of strongly catholic family into a relatively guilt free agnostic - more at ease with the world.

So he left for London and soon found work there, contributing to the Sunday Times and later the Sunday Telegraph. He was scathing of the youth underground of the sixties in London which he claimed was based on spontaneous hedonism, the joy of marijuana, spontaneous and uncommitted sex, and culturally illiterate, ignorant of most things older than itself. And it was within this milieu that Hughes met his future wife, Danne Emerson.

Danne Emerson (xwhos.com)

The marriage was a disaster. Emerson was also an expat Australian with a Catholic upbringing. Shortly after the birth of their son Danton, Danne announced that she was going to ‘find her own fucks’ and suggested the Hughes do the same. “If there was ever a misalliance between two emotionally hypercharged and wolfishly immature people. It was our marriage. I was as unsuited to her as she was to me. I could no more fulfull or even predict her needs than she could mine.”

He blames his Catholic upbringing for lacking the courage to end the marriage, at least until 1981. He said it was like being trapped in the hull of an upturned boat, running out of oxygen yet lacking the courage to dive deeper and escape to the surface. He claims she contracted the clap from Jimi Hendrix before passing it on to him. But Hughes’ own track record wasn’t spotless and this was another reason for his reluctance to file for divorce - fear that Danton might become a ward of the courts.

He is scathing of Brett Whiteley who, he suspected, introduced Danne to harder drugs which was the final nail in the marriage coffin. He found a drug-free Whiteley to be delightful company but “The shame of addiction…is apt to make junkies into missionaries. They like, and need, to drag others down with them. Such aggression compensates for their own weakness and dependency with drugs.”

Hughes describes Whiteley as a cultural mascot for the semi-cultivated, a disciple (supposedly) of Zen Buddhism who overdosed in a lonely motel room south of Sydney. Danton died by suicide in 2001 with Hughes once claiming that they hardly knew one another. Danne died in 2003 from a brain tumor.

The Interior of the Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence (The Guardian)

One of the most significant experiences of Hughes’ life was when he reported on the devastating Florence floods of November 1966 for BBC2. The flood laid waste to much of the rich cultural heritage of Florence and imbued in Hughes an even greater reverence for art of the past and an antipathy for those of the avant-garde who regard the past as repressive and a dead weight that ‘new’ art had to shake off. He acknowledges that culture does change but the idea that it can reinvent itself, like a snake shedding its skin is naïve. He is regarded by some as a cultural conservative.

Perhaps it was his enquiring, encyclopedic mind that prevented Hughes from reigning in his story to one volume, but it’s worth a read nevertheless.