The current shutdown has given me an opportunity to reflect on an exhibition held at Tarrawarra Museum of Art last year; Tracey Moffatt’s Body Remembers photographic series and her video work Vigil both of which received acclaim at the 2017 Venice Biennale.

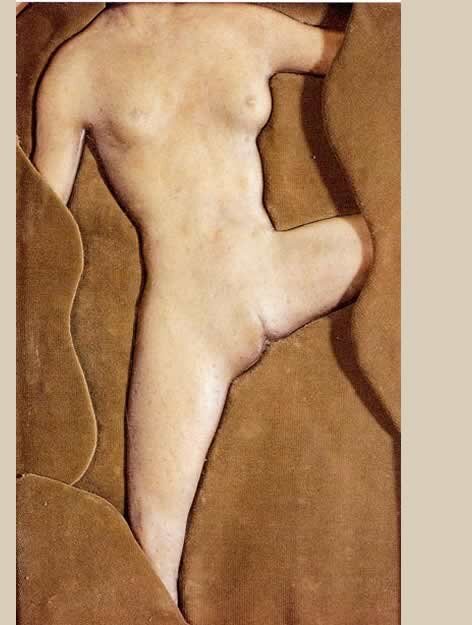

Walking into the space, there was a strong sense of alienation pouring out of these 10 sepia-hued photographs, of displacement and discord. A lonely domestic figure (played by Moffatt) in an abandoned homestead seemingly in the middle of nowhere. The colour of the walls was obviously chosen to emphasize the sombre mood of the exhibition. Yet the photographs are also highly evocative, there is a sense of longing and sorrow.

Why has she been left behind, or has she returned? What was she doing there in the first place?

Moffatt rarely gives interviews, but a Sydney Morning Herald article tells us that in preparing the series of photographs she created a diagram or mind map listing her various ideas and influences;

“Desert and silence”

"Essays about the ruin in art that I have never read."

"The back of women's necks."

"The history of Mount Moffatt Station – the former vast cattle station in Queensland where some members of my family worked in 1910 – of which I know nothing."

"De Chirico – shadows of the afternoon."

She also mentions the film Black Narcissus, the works of Andrew Wyeth and Martin Scorsese, glass-plate photography, Irish lace, Spain, Egypt, and various film scenes and actors. A disparate list indeed, yet you can see many of these influences in the final series.

We never see Moffatt’s face, instead we either see her in the distance from behind or she is gazing away from us. According the Tarrawarra’s director Victoria Lynn, this emphasises one of the central themes of the photos: the collision of looking and being looked at.

"It is as if the woman portrayed is returning to the place where she used to be a servant, returning to that place of servitude, remembering the trauma," Lynn says. "She is looking and gazing in various directions away from the camera but she is also aware that we are looking at her.”

Moffatt was born to an Indigenous Australian mother and an Irish father in 1960, but was adopted into a white family in the suburbs of Brisbane at age three. Her birth mother would visit her and accustom her to Indigenous identity, thus allowing her to take part in two separate cultures growing up.

This exhibition is at once personal and universal, referencing the stolen generation. This is not a new theme for Moffatt. Her 1989 series Something More referenced the forced removal of young Aboriginal women from their families and their internment as domestic servants on rural properties.

Tracey Moffatt describes Body Remembers as ‘a play with time, backwards and forwards of the past and present’. She appears to be exploring the legacy of colonisation, of resulting intergenerational traumas and their reverberations across time and place.

It was one of those exhibitions where viewing it alone seems to be the only option. The carefully constructed compositions allowing the viewer to absorb the loneliness and the sense of simply being out of place.

References;

Sydney Morning Herald

Tarrawarra Museum of Art

Mosman Art Gallery