A friend once said to me many years ago “It’s a pain in the backside when you are driven to do something that’s not economically viable”. By which he meant - art. But then, perhaps it depends on what type of art practice we are talking about.

When I was at art school in the 1990’s, I was made aware of an exhibition called the Cunningham Dax collection of psychiatric art that was on show at the Victorian Artists Society in East Melbourne. Talk about art on the edge!! Years earlier, the head of the mental health authority in this state, Eric Cunningham-Dax, had rescued from the dumpmaster hundreds of drawings and paintings produced by patients of psychiatric hospitals. They are now on permanent display at the Dax Centre, Melbourne University. The last time I saw the exhibition, it had been sanitized compared to what I saw years before. That is, not half as confronting.

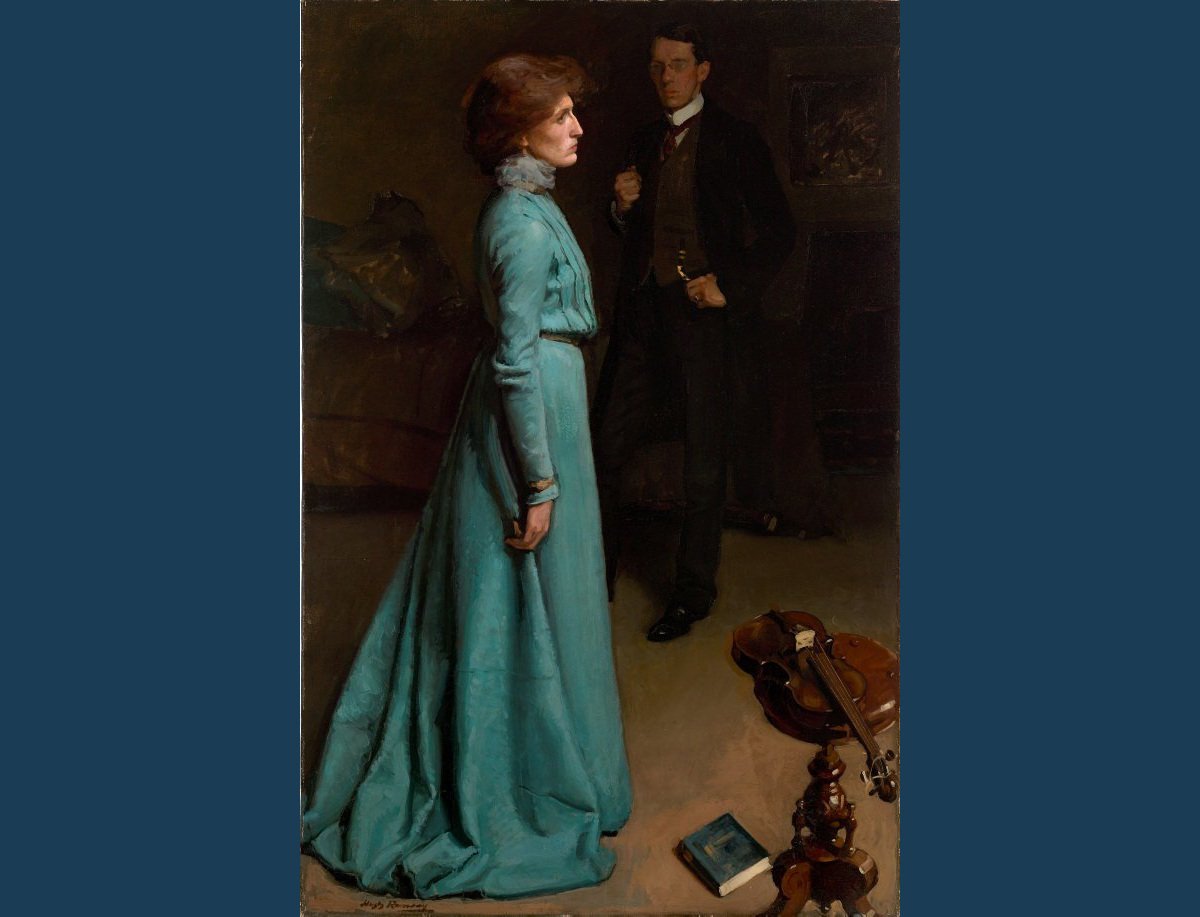

Evening At Aradale, 2007 oil on canvas, 80 x 106 cm

The whole issue of mental illness, of an existence outside the mainstream, has long fascinated me. Not to mention the history of mental illness in my family. (Given recent events, I would imagine the prevalence of mental illness has skyrocketed generally.) In the early 1990’s I attended an open day at the Willsmere Psychiatric Hospital in Kew just after the last patients had been removed. Unforgivably, I left my camera home. I didn’t make the same mistake when I visited the former Aradale facility in Ararat in western Victoria a few years later.

View From The Tower, Aradale, 2021, oil on canvas, 84 x 84 cm (available for sale on the Bluethumb website)

Aradale certainly attracted its fair share of adverse publicity over the years, largely due to underfunding by increasingly stingy governments. It was opened for business in the late 1860’s and in its heyday was surrounded by 100 acres of land. The facility raised its own cattle, sheep and poultry, did its own slaughtering, grew fruit and vegetables and thus was largely self-supporting. Coal for the furnaces was about the only thing that needed to be brought in, apart from patients of course. The facility also had its own tailors producing uniforms, a chapel and a morgue.

Winter At Aradale, 2021, oil on canvas, 66 x 86 cm (available for sale on the Bluethumb website)

Whilst facilities such as Aradale courted controversy from time to time, there is no doubt that “asylum” means refuge and sanctuary and many of the former patients would stand little chance of surviving in the outside world. The notion of “least restrictive environment” governs mental health policy these days, thus we have the reality of “sidewalk psychotics” as the Americans call them.

I held an exhibition of paintings based on Aradale at the Ararat Gallery in 2004. One of the gallery staff told me she drove past the entrance to Aradale the morning after it had closed in 1993 and saw what she believed to have been former patients gathering at the gates. They may have been crazy, but they weren’t stupid.

Aradale Evening, 2022, oil on canvas, 71 x 86 cm (available for sale on the Bluethumb website)

Some year ago I got fully involved in exploring ‘issues’ in my art and was producing rubbish more often than not. So while the issue of deinstitutionalization still lingers in the back of my mind, (as I see it as a symptom of a less caring society), I’ve learned to focus on the art. Perhaps it’s better to cajole someone to a particular point of view rather than browbeating them.

Hello, my name is Geoff. You may be interested to know that I’m a fulltime artist these days and regularly exhibit my work in Victoria, but particularly in Melbourne. You may wish to check out my work using the following link; https://geoffharrisonarts.com