I’ve discovered that Salvador Dali and Vincent Van Gogh have something in common, apart from being artists of course. They were both born shortly after the deaths of an infant brother. Both inherited the same Christian name as their deceased sibling and whether this accounts for their bizarre behaviour is open to conjecture, but it has been argued that Vincent was raised by a grieving mother.

In Dali’s case, the family, particularly his mother, grandmother and aunt, doted on him, wrapping him in affection and allowing him every indulgence. Dali soon learned how to turn this situation to his advantage by regularly throwing tantrums in order to get his own way.

Dali had a particularly close attachment to his mother Felipa Domènech, an artist who drew competently and crafted exquisite wax figurines out of coloured candles. Felipa’s death in 1921 when Dali was 16, and his disciplinarian father’s subsequent marriage to his aunt had a devastating effect on him and he looked to his younger sister, Ana Maria as the pivotal female figure and mother substitute in his life.

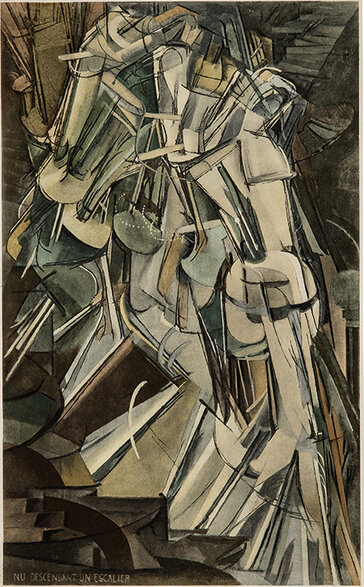

Figure At The Window (1925), oil on papier mache, 105 cm x 74.5 cm

Dali was 21 when he painted this scene and Ana Maria (three years his junior) was Dali’s only model until his future wife, Gala arrived on the scene. I love the cool light pervading this scene as well as the superb draftsmanship. Ana Maria claimed that she didn’t mind sitting for hours for her brother and the experience gave her an appreciation of landscape.

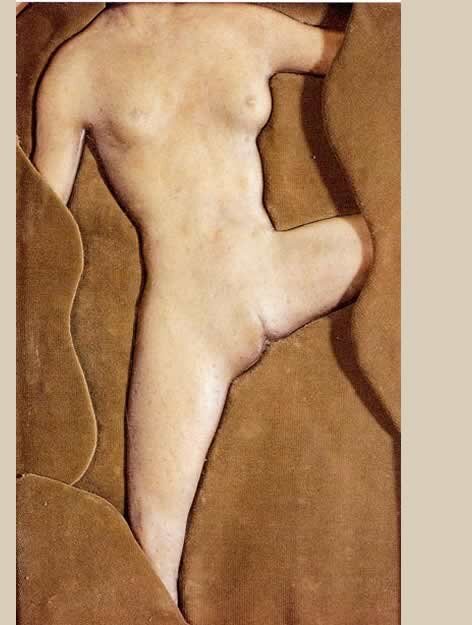

Figura De Perfil (Figure In Profile) 1925, Oil on cardboard, 74 x 50 cm

Dali had been showing signs mental illness by 1929 and it was in this context that he first met Helena Diakanoff Devulina (Gala) who was a Russian immigrant, 10 years older than he and well known to the surrealists, and who became Dali’s lifelong partner until her death at the age of 88. She became his muse, wife and (supposedly) business manager. Both Ana Maria and their father detested her. The fact that Gala was somewhat older and already married when she met Salvador was probably the main issue here. According to The Guardian, during the Spanish civil war, Ana Maria was briefly arrested and imprisoned by the Republican forces and she believed Gala had denounced her falsely as having fascist sympathies. The irony is that Salvador appeared to be one of Franco’s most enthusiastic supporters.

She also took issue with one of her brother’s notoriously unreliable memoirs where he wrote of a troubled childhood and a tormented relationship with their father. She in turn published her own memoir in 1949 Salvador Dali As Seen By His Sister which left him enraged by her portrayal of his childhood as normal and happy.

Young Virgin Auto-Sodomized By The Horns Of Her Own Chastity, 1954, oil on canvas, 40.5 x 30.5 cm

This was Dali’s response to his sister’s memoir and is thought to be inspired by an image in a pornographic magazine. This time we see Ana Maria being assaulted by flying phalluses.

Dali survived for seven frail, miserable years following the death of Gala in 1982. He was isolated (it’s claimed he drove away most of his friends) and was almost penniless. He and Gala were spendthrifts with the concept of investing being foreign to them. It was thought that fame, not money, was Dali’s primary motivation. There are doubts as to the authenticity of many of his prints due to his habit of signing blank sheets of printing paper in his final years.

Salvador and Gala, Dali Museum

After decades of zero contact between them, Ana Maria visited her brother in hospital on what was thought to be his death bed in 1984. The result was a raging argument between the two of them with Dali having her kicked out of the room. They never met again and Dali died of heart failure in his home at Figueres in 1989. Ana Maria survived him by five months.

References;

BBC Omnibus

National Gallery of Victoria Educational Resource

The Guardian